THE 19th SACRED MIRROR: CHRIST

Jesus said, “When you make the two one, and when you make the inside like the outside and the outside like the inside, and the above like the below, and when you make the male and female one and the same… then you will enter the Kingdom of God.”

Gospel of Thomas

Created during the early 1980s, Alex Grey’s painting of Christ is part of a twenty-one life-sized framed images, the installation of the Sacred Mirrors series, currently residing in the Chapel of Sacred Mirrors. Just like the other images, Christ is forty-six by eighty-four inches and presents a life-sized figure directly facing the viewer, arms to the side and palms forward. “This format allows the viewer to stand before the painted figure and “mirror” the image. A resonance takes place between one’s own body and the painted image, creating a sense of “seeing into” oneself” (Grey 32). The series of twenty-one paintings can be divided into three sections: Body, Mind, and Spirit. Grey sought to present a journey-like experience as viewers progress through the Great Chain of Being — and the experience is essentially this: the unfolding and developmental sequencing from the lower to the higher modes of knowing and perceiving. It is as Wilber notes, the transpiration of the different eyes: “the eye of flesh, which discloses the material, concrete and sensual world; the eye of the mind, which discloses the symbolic, conceptual and sensual world; and the eye of contemplation, which discloses the spiritual, transcendental world” (Grey 9). Viewers progress from sensibilia (phenomena that can be perceived by the Body), to intelligibilia (objects perceived by the Mind), and in breaking the ego, activates transcendelia (spiritual perception). The Christ painting is situated in the spirit section alongside a painting of Avalokitesvara and Sophia. And although the artist’s medium is almost always sensibilia — for the work is within the realm of matters: paint, canvas, linen etc. — the critical question, as Wilber puts it, is this: “Using the medium of sensibilia, is the artist trying to represent, depict or evoke the realm of sensibilia itself, or the realm of intelligibilia, or the realm of transcendelia? … we add the crucial ontological question: “Where on the Great Chain of Being is the phenomenon the artist is attempting to depict, evoke, or express?” (Grey 10).”

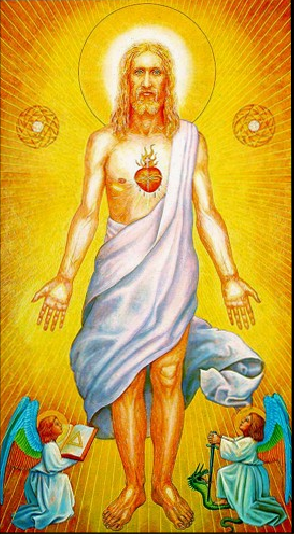

“In the Sacred Mirrors, Christ is shown resurrected, surrounded by golden light, with two angels: Gabriel (left) is holding a book on which a symbol of the trinity appears; Michael (right) exhibits the compassion that subdues evil but does not kill it. A flaming infinity band of love encircles the Sacred Heart, and whirling six-pointed stars on either side of Christ’s head refer to Christ’s mystical origins. The six-pointed star symbolizes the primal unity of heaven and earth and the divine Father and Mother. According to the Gnostic Gospels, Christ taught that the Godhead was both male and female; he referred to both his heavenly Father and Mother (which has become the Holy Ghost or Holy Spirit).” (Grey 38)

Grey’s Christ is spiritual in the deepest sense. Thus, in answering the question posted previously, it is situated on the highest hierarchy on the Great Chain of Being. It does not seek to merely portray a highly stylized Jewish messiah, nor two calm-colored angelic figures, nor random placement of mystical religious symbols; it does not seek to educate the eye of the mind and provide intellectual nourishment nor does it seek to merely disclose “the world of ideas, symbols, concepts, images, values, meanings, and intentions (Grey 9)”; rather, “it springs from the dimension of nondual and universal Spirit, which transcends (and thus unites) both subject and object, self and other, inner and outer… Art created in this nondual awareness offers direct access to nondual Spirit” (Grey 14). It is as Grey intends it: “to realize and activate the essential truth that [Christ] was ([as]we are) “The Word made flesh” — a direct channel for the love and healing energy of God” (Grey 37). As Beckett recapitulates — concerning spiritual arts in general — “This understanding may well be activated, intensely so, but in the activating a real change takes place. The vehicle, to repeat the image, moves on its own. Whatever the conceptual insights that accrue to those who practice their religion, the pictorial power comes non-conceptually. It effects what it signifies… but the mind may be aware only of the impact of some mysterious truth. This is the essence of spiritual art. We are taken into a realm that is potentially open to us, we are made more what we are meant to be” (Beckett 7).

POST-MODERNISM: SEEKING EVOLUTION RATHER THAN REVOLUTION

Before understanding Grey’s Christ, I believe it is essential that we first come to terms with the context and conventions that which inspires the aspirations of the artist. Plunged in an era of ‘ism’s, the “Post-Modern Age is a time of incessant choosing” (Jencks 7). Once in Modernism we see the repudiation of all traditional styles that preceded it, and this is evident in the various art movements that sprang like mushrooms during that era: cubism, surrealism and the notorious dadaism to name a few, now we see yet another tide of change. An overture that seeks “to take stock of the old as well as absorbing the shock of the new” (Collins 9). We, as Collins notes, “stand at a point where it may be avant-garde to be rear-guard. We are searching for a design vocabulary which extends beyond basic language and basic structure.” And in this search, confusion is inevitable. The job at hand is thus to eclect traditions from the past and present. If successful, it “will be a striking synthesis of traditions; if unsuccessful, a smorgasbord” (Jencks 7). This characteristic of eclecticism does so little at alleviating the confusion than it is at exacerbating it. Notice Jencks’ apparent lack of definition for the value of the word “successful.” Who, where and what are the defining line(s)? Thus here, amidst the confusion we see that it is the bearing of subjectivity in which we are so open to that ultimately and fundamentally sets us assail, as Jencks notes, on a scale “between inventive combination and confused parody… often getting lost and coming to grief.” Nonetheless, upon this plane of infinite possibilities the combination and permutation of the past and the present grants, one cannot deny the “great promise of a plural culture with its many freedoms.” Indeed, “pluralism, the ‘ism’ of our time, is both the great problem and the great opportunity” (Jencks 7).

For some, Post-Modernism killed Modernism. For others, it is an extension. My opinion lies with the latter. Taking a cue from Efland, “if modernism is the style that repudiates past styles, then the postmodern style that repudiates the modern can be seen as maintaining the modern tradition” (Efland 11). From this logic, how can one movement repudiate another while maintaing the essences of the repudiated? It is only reasonable to view Post-Modernism as an extension of Modernism. In Postmodern Art Education: An Approach to Curriculum, Efland forwards Jencks‘ use of hyphenation “because [Jencks] believes that post-modern art still contains many aspects of modern art, but these have been added to, adopted, or embellished… [thus] by hyphenating the word, “modern” maintains its integrity as a word” (Efland 31). Defining Post-Modernism, Jencks claims that it is “that paradoxical dualism, or double coding, which its hybrid name entails: the continuation of Modernism and its transcendence” (Jencks 10). In this convention of confusion, Alex Grey finds himself ‘eclecting’ traditional Sacred Art and Psychedelic Art — a fusion which produces the unique Visionary Arts of the Sacred Mirrors.

SACRED ART: SPIRITUAL HEALING

“… the Now of our present life and the mystical closeness of God can seem in opposition. The Now is down here, material, busy about many things, pressured. The Mystical is up there, spiritual, free floating… St. Augustine held that the human heart is restless until it finds rest in God” (Beckett 5).

In The Mystical Now Art and The Sacred, Beckett highlights the disparity between religious art and spiritual art. According to his theory, “religious art, that most demanding of the genres, may bring us to prayer by virtue of its religiousness rather than by its art” (Beckett 6). How one is effected by the art depends on his/her depth of faith. Religious images are seen as art that instigate the viewers to pray. They “do not necessarily take the believer any further. They do not per se, deepen the faith of those who contemplate them – they [merely] activate it.” Thus, the quality of the art is not of highest priority. Beckett’s case illustration of the Russian Orthodox use of the ikon best exemplifies how the art “is in itself an act of profound faith [as] the artist prays and fasts, preparing his or her heart for the work of devotion that will be the painting.” Wilber, in regard to Grey’s Sacred Mirrors series forwarded Michelangelo’s selfsame belief: “…it is not sufficient merely to be a great master in painting and very wise, but I think that it is necessary for the painter to be very moral in his mode of life, or even if such were possible, a saint, so that the Holy Spirit may inspire his intellect” (Grey 12).

Spiritual art on the other hand, is “the artistic depiction/expression of [the artist’s own soul, right up to the point of union with universal Spirit and transcendence of the separate self or individual ego], particularly in such a way as to evoke similar spiritual insights on the part of the observers” (Grey 13). As Beckett points out, “it is this truth… that makes spiritual art so important to us. It is not a substitute for religion, but for those who have no other access to God it is a valid means of entering into that numinous dimension that alone makes the ‘incomprehensibility’ not only bearable but life-giving” (Beckett 9).

Grey’s Christ is both religious and spiritual in its essence. Though non-believers may comment on the 2-dimensional cartoonish portrait as one of a severe lacking in artistic skills, the radiating light from the Christ’s head and body are sure reminders to believers that “[He is] the light of the world,” John 8:12. It is as Beckett notes: “By illustrating, [the image] reminds, and the believer wants that reminder, takes it gladly and uses it as a means to God. For the believer as such, the actual quality of the art is unimportant – the work stands or falls by its ability to raise the mind and heart towards truths of faith” (Beckett 6). Upon further contemplation on the Christ figure, the light begins to encapsulate the viewer, and the art does not reside in simply raising the “mind and heart towards truths of faith”, but transcending the realms of sensibilia and itelligibilia, these truths of faith is alleviated into the realm of transcendelia. In my personal experience, and perhaps this is by and large due to the way the Sacred Mirrors book is designed, to lead from body to mind, and mind to spirit, and the juxtaposition of Christ in between Avalokitesvara and Sophia, I suddenly felt a deep connection from within my own personal faith as a Christian and to that of the other faiths — as if breaking out of my comfort zone, the cage in which I was brought up to believe in that if I leave, I will go to hell… my spirit wandered and contemplated the idea — and this was an area I had never dreamed to venture — that perhaps just like many rivers that lead to the selfsame blue expanse we call “sea”, so does our religions lead to one universal Godhead. The experience was bewildering and I must admit that I’m still in that phase of confusion. Echoing the words of Beckett, “[perhaps this] is also why so many people unconsciously fear and resist art. We may not want to become aware of suppressed and unrecognized aspects of ourselves… fallen creatures, ego-lovers, nomads in a world that we both love and feel alien to… ‘We have forgotten who and what we are.’ And art… ‘makes us remember that we have forgotten.‘ This is painful. It is also our best means, apart from direct contact with God, of discovering that interior integrity” (Beckett 9). Reiterating Grey’s purport, Christ is essentially a painting for viewers “to realize and activate the essential truth that [Christ] was ([as]we are) “The Word made flesh” — a direct channel for the love and healing energy of God” (Grey 37).

PSYCHEDELIA: PEEPING INTO THE ANTIPODES OF THE MIND

“On June 3, 1976, we simultaneously shared the same psychedelic vision: an experience of the Universal Mind Lattice. Our shared consciousness, no longer identified with or limited by our physical bodies, was moving at tremendous speed through an inner universe of fantastic chains of imagery, infinitely multiplying in parallel mirrors. At a super-orgasmic pitch of speed and bliss, we became individual foundations and drains of Light, interlocked with an infinite omnidirectional network of fountains and drains composed of and circulating a brilliant iridescent love energy. We were the Light, and the Light was God.”

Allyson and Alex Grey

According to Robert E.L. Masters and Jean Houston’s Psychedelic Art, “the psychedelic artist is an artist whose work has been significantly influenced by psychedelic experience and who acknowledges the impact of the experience on his work” (Masters 17). Both authors furthers the idea that the provision of “intelligence, feeling, imagination, and talent” (Masters 18) is made by the artist and not the chemical. The psychedelic experience is merely another experience, though the artist may draw inspiration from it just as he or she draws inspiration from any other experiences. “Where artists of the past traveled to the ends of the earth, these new artists travel inward, to what Aldous Huxley called the antipodes of the mind – the world of visionary experience” (Masters 18).

In the case of Alex Grey, his artworks aren’t so much as a fusion of psychedelia and spirituality as it is a derivation of one from the other. Though psychedelic substances does not necessitate a spiritual experience, and hence give birth to spiritual art, its potential to do so is unquestionable. Though to some, psychedelic experience is merely the feeling of a distorted consciousness, many however regard the alteration of consciousness as a means to withdraw from the individual self and to be in tandem with the universal self, “a transformative contact with the Ground of Being” (Grey 31). Hence, psychedelic experience isn’t just the experience of a distorted mind but rather, a mystical one. As Masters and Houston note: “The art is religious, mystical: pantheistic religion, God manifest in All, but especially in the primordial energy that makes the worlds go, powers the existential flux. Nature or body mysticism: the One as an omnisensate Now (Masters 81).” And in very much the same way shamans employ methods of “intoxication, sex, nudity, physical abuse, and self denigration” (Grey 18) to contact the spirit world, one of Grey’s “portals to the mystical dimension” is psychedelic drugs. Reiterating what I said before, spirituality is in Grey’s case, derived from psychedelia. His psychedelic visionary artworks in the Sacred Mirrors series is thus also, his spiritual mystical artworks. They all convey “the spectrum of consciousness from material perception to spiritual insight; and function… as symbolic portals to the mystical dimension” (Grey 31).

THE TRANSFIGURATION OF VELZY TO GREY

Born Alex Velzy, young Alex had demonstrated extreme concern towards the polarity that existed within the self and the universe; a monomania towards the opposing forces of spirit and matter. For the most part of his adolescent years, he was “consumed by the idea that the conflict of opposites was the underlying principle of the cosmos” (Grey 20). This lead to various formalized insights regarding polarities, chiefly the polarity of life and death. As Jung has noted, “Just as all energy proceeds from opposition, so the psyche too possesses its inner polarity, this being the indispensable prerequisite for its aliveness… Both theoretically and practically, polarity is inherent in all living things.” Similarly, the philosophy of Taoism states that the macrocosm as well as the microcosm is constructed on the principle of complementarity expressed as Yin and Yang (Grey 20). This monomania towards polarity, evident even in his early artworks — as early as 5 years old! — slowly consumed him, driving him into madness. Essentially, it was as Grey exclaims, “a search for ‘something’.” Perhaps it was to gain insightful understanding of the two opposing forces, perhaps it was find a place between the two forces, perhaps it was to discover a language unbounded by the principles of polarity… “As the polarity pieces developed, Grey’s shamanic method of personal realization, or what could be interpreted as a descent into madness, was greatly intensified” (Grey 20). This however, ended with Polar Wandering, a pilgrimage to the North Magnetic Pole where he ran nude in circles after the needle of a compass which, due to the convergence of magnetism, had spun hysterically. In regard to the out-of-body trance state he experienced within himself while performing the ritual, Grey expressed: “I felt I had dissolved into a pure energy state and become one with the magnetic field surrounding the earth” (Grey 13).

“After I returned from the North Magnetic Pole, flat broke, I realized that my performance were an exhaustive desperate search for ‘something.’ And although I called myself an agnostic existentialist, I challenged “God, whatever that is” to appear to me. Within twenty-four hours the following two life changing events occurred: At a party I took LSD for the first time. Sitting with my physical eyes closed, my inner eye moved through a beautiful spiraling tunnel. The walls of the tunnel seemed like a living mother of pearl, and it felt like a spiritual rebirth canal. I was in the darkness, spiraling toward the light. The curling space going from back to gray to white suggested to me the resolution of all polarities as the opposites found a way of becoming each other. My artistic rendering of this event was titled the Polar Unity Spiral. Soon after this I changed my name to Grey as a way of bringing the opposites together.”

Alex Grey

This theme of ‘resolute’ polarity became one of the many themes apparent in the Sacred Mirrors series. In Christ, the existential polarity of good and evil as depicted through the symbol of the trinity on a book Gabriel (left) bears and the demonic serpent upon Michael’s (right) foot form the base of the triangular shape in which the Christ figure and the angelic figures form, combined. These opposing forces however, is given very little regard as the angels’ gaze are on neither but rather, adjusted upward towards the messiah’s head, the zenith of the triangle. Thus, Grey conveys the idea that the struggle of polarities are but base concerns in the light of divinity. The spiritual or universal, is nondual. When contemplating on Christ, “the viewer momentarily becomes the art and is for that moment released from the alienation that is ego. Great spiritual art dissolves ego into nondual consciousness, and is to that extent experienced as an epiphany…” (Grey 14).

A BRIEF COMMENTARY ON CHRIST

One of the common traits of Post-Modernism is the practice of “appropriation”. “Loosely, appropriation refers to the artistic recycling of existing images” (Getlein 553). In the case of Christ, the central figure of the messiah is Grey’s recycling of existing Christian images. Appropriating the messiah to incorporate numerous other symbols (i.e. the Eye of Providence, the Star of David, the Holy Trinity etc.), Grey thus creates a Christ figure that is both familiar and alien at the same time. The figure retains nuances of old conventions of portrayal as such the long curly hair, thick beards, robes, and the use of halos but nonetheless offers novelty in that we see the replacement of nail-holes with the Eye of Providence symbol, illumination of scars and Grey’s own unique “infinity band of love.” Reiterating Jencks‘ definition of Post-Modernism art, it is “that paradoxical dualism, or double coding, which its hybrid name entails.” Interpreting “paradoxical dualism” as “nondualism”, Grey’s Christ depicts essentially the contradictions as non-contradictions: the old as new and the new as old, both sides assimilated as one.

This concept of nondualism, “polar unity” as Grey coins the term, can also be seen through the depiction of space within the image. Here, finite space coexists with infinite space. While space is depicted through the radiating light, lines that converges toward the figure’s heart, the somewhat cartoonishly painted figure and the highly symmetrical balanced posture (even the robe draping to the left is balanced with the float on the right!) makes the image appear extremely flat. Ergo one may actually see depth and no depth at the same time; space and no space simultaneously. Furthermore, there are four triangular shapes in the image, all which functions as not only symbolic conception, but also arrows that imply lines that direct the viewers point of sight. As mentioned previously, the Christ figure along with the two angelic figures forms an illusionary triangular shape with the head of the Christ at the shape’s zenith. The other three traingulars can be found on the messiah’s palms and on the book. Note that all three of these triangulars point upwards towards the messiah’s head. It is only natural that the viewer, facing the life-sized image of Christ, winds up contemplating on the messiah’s face… staring deep into the figure’s illuminated eyes and have them stare back, activating — if even for a moment — the viewer’s spirit into the realm of transcendelia.

“The artist must train not only his eye but also his soul, so that it can weigh colors in its own scale an thus become a determinant in artistic creation” (Grey 13). What impresses me the most of Grey’s Christ is not merely his ability to select and mix colors of high values but rather, the ability to illuminate them. At close inspection, one will notice that upon the messiah’s skin are thousands of small stripes of brushstrokes, lacerations of colors such as light blue, green, indigo etc. – colors that has very low intensity. Up front, these strokes of random colors look extremely out of place upon the brownish-yellow color of the figure’s skin. From a distance however, the effect of “optical color mixture” sets in. Loosely speaking, it is the effect of the eye blending different colors that are close together to produce a new color (Getlein 99). Thus, instead of weird nonsensical colors randomly scattered around the image, the viewer’s eyes registers them as one color: the color of illumination. It is the kind of color that looks like a bright light, glowing off the surface of the Christ. I personally find Grey’s incorporation of this optical illusion technique to be extremely captivating.

SOME CONCLUSIONS

“A shaman is one who embarks on a path that challenges the norms of society – its values, imagery, and scared cows – in order to achieve the healing powers and wisdom that are its goals. He or she stands in opposition to society’s highly developed, mutually agreed upon perception of reality that forms the collective dream of sleepwalking humanity.

Transculturally, the shamanic process involves an initiatory phase in which the shaman meets his/her animal allies and descends to the underworld. After confronting death in some dramatic event he/she is “reborn” and ascends to the higher worlds to meet helpful spirits. Along the way the shaman receives his or her healing powers and visions” (Grey 18)

Carlo McCormick

I personally love the shaman analogue McCormick draws to that of Grey’s transfiguration. More than the artworks, my deep appreciation towards Grey lies within the story of his life as an artist. The constant questioning; the passion and drive in search of that “something”, as McCormick compares it to the shaman’s path, which placed Grey at the brink of Madness; the necessary strides of confusion… Whenever I look at Christ, or any images from the Sacred Mirrors series for that matter of fact, it is not the transcendental abilities of the images that inspires me — though I do not deny the fact that Grey’s mastery in expressing the Spirit is no less than profound — but rather, the transfiguration which is so immanent behind every brush stroke. The transfiguration of a confused boy, a boy in search of that “something”… I don’t really know how to explain this feeling I get when I look into Grey’s artwork. Somehow, whenever I flip through my Sacred Mirrors book, I don’t feel alone… I feel… understood.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beckett, Wendy. The Mystical Now Art and The Sacred. New York: UNIVERSE, 1993.

Collins, Michael. Towards Post-Modernism. New York: New York Graphic Society, 1987.

Efland, Arthur, Kerry Freedman, Patricia Stuhr. Postmodern Art Education: An Approach to Curriculum. Virginia: The National Art Education Association, 1996.

Getlein, Mark. Living with Art. 1985. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008.

Grey, Alex, Ken Wilber , and Carlo McCormick. Sacred Mirrors The Visionary Art of Alex Grey. Vermont: Inner Traditions International, 1990.

Grey, Alex. Transfiguration. 2001. Vermont: Inner Traditions International, 2004.

Jencks, Charles. What is Post-Modernism? 1986. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1987.

Masters, E.L. Robert, and Jean Houston. Psychedelic Art. New Jersey: Balance House, 1968.

1 Comment so far

Leave a comment

Duude! I finally finished reading this essay… great work man… i recently read some very similar stuff about the shaman that Terence McKenna wrote…and i get what u mean…the constant search for the answer…and the transfiguration that occurs on the way to realizing your true Self…

Comment by Adrian May 19, 2009 @ 12:15Anyway…you got a book on the Sacred Mirrors! Thats awesome man…Where’d u get it?